The housing crises

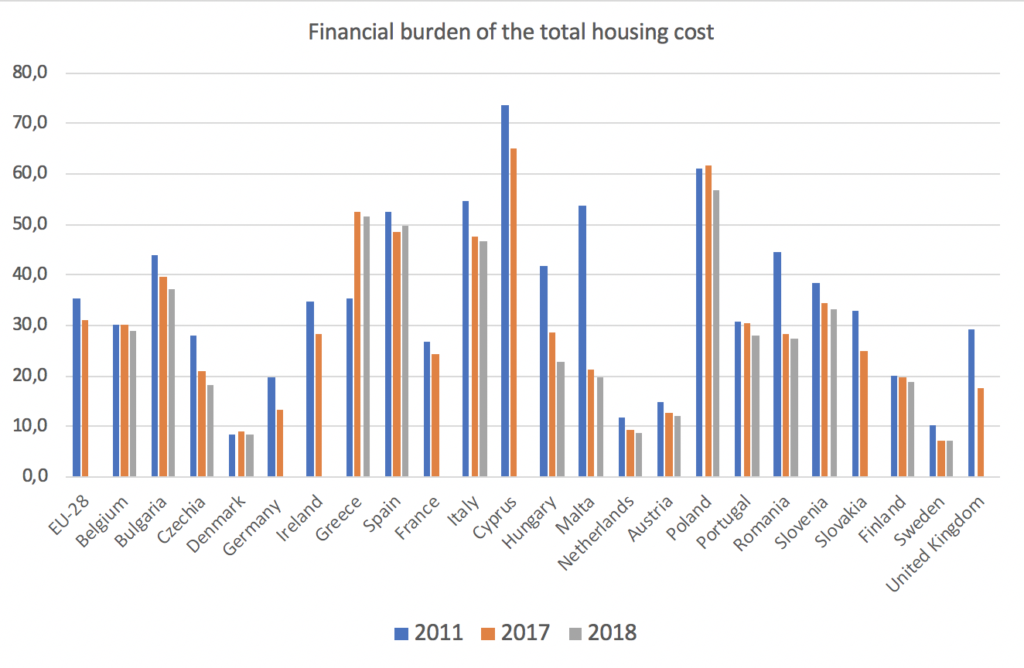

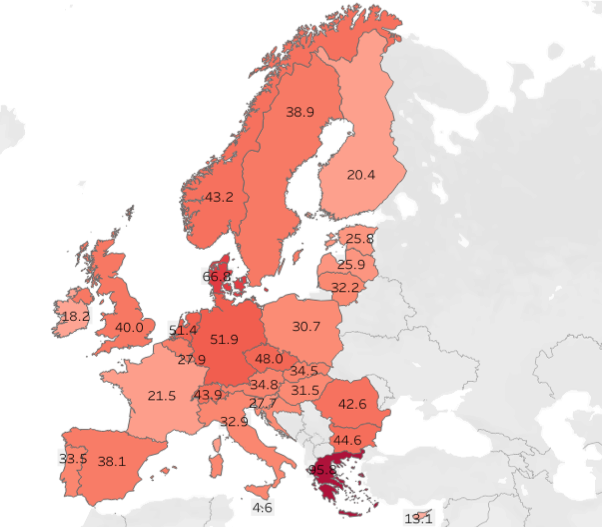

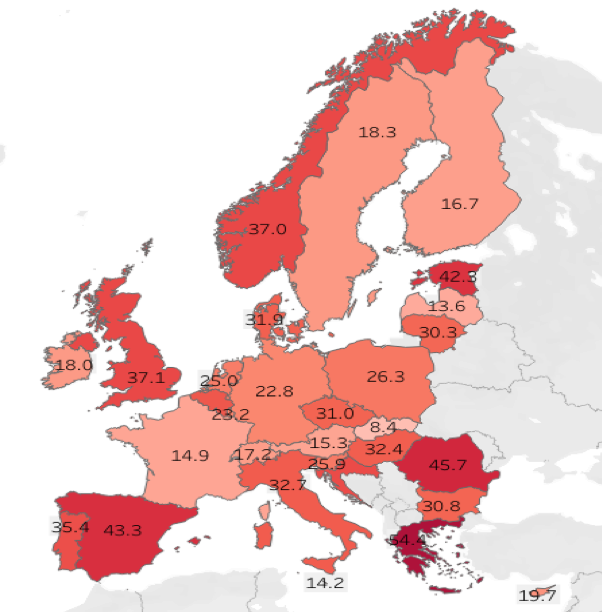

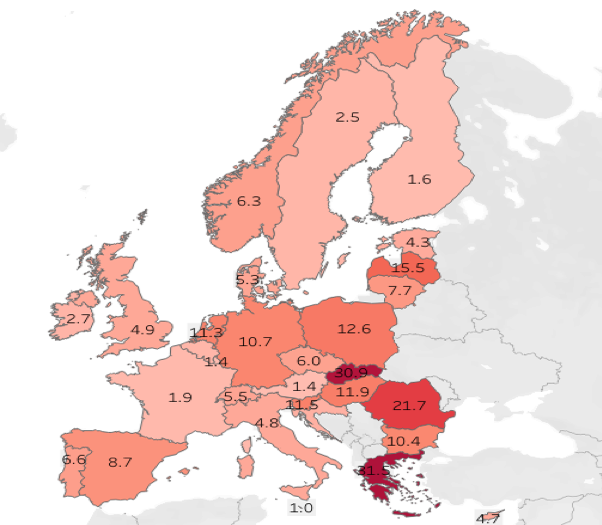

During the decade following the 2008 global financial crises, international organizations with a fundamental role in shaping financial and development policies – such as the European Commission, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund – recognized the persistence of housing crises across all the countries of the world. It is easy to observe that the rates of the financial burden of the total housing costs1 are unevenly distributed among the EU Member States (Fig. 1). Moreover, the housing cost overburden rate2 is exceptionally high among people at risk of poverty (Map 1), but it is also worrying among households who are renting their home from the market (Map 2) and among homeowners with mortgages (Map 3).

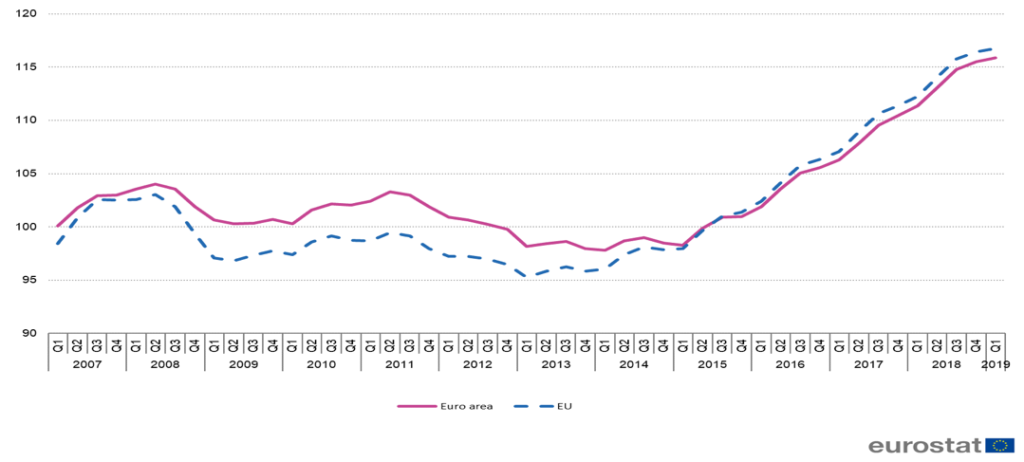

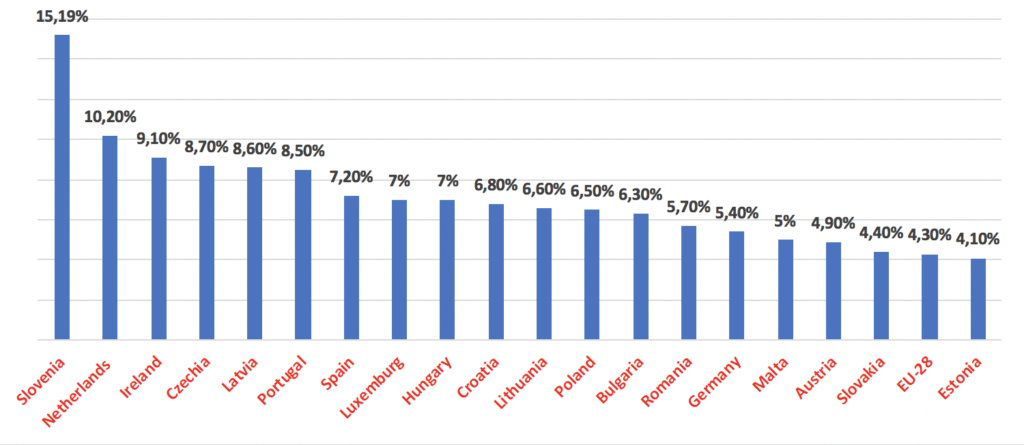

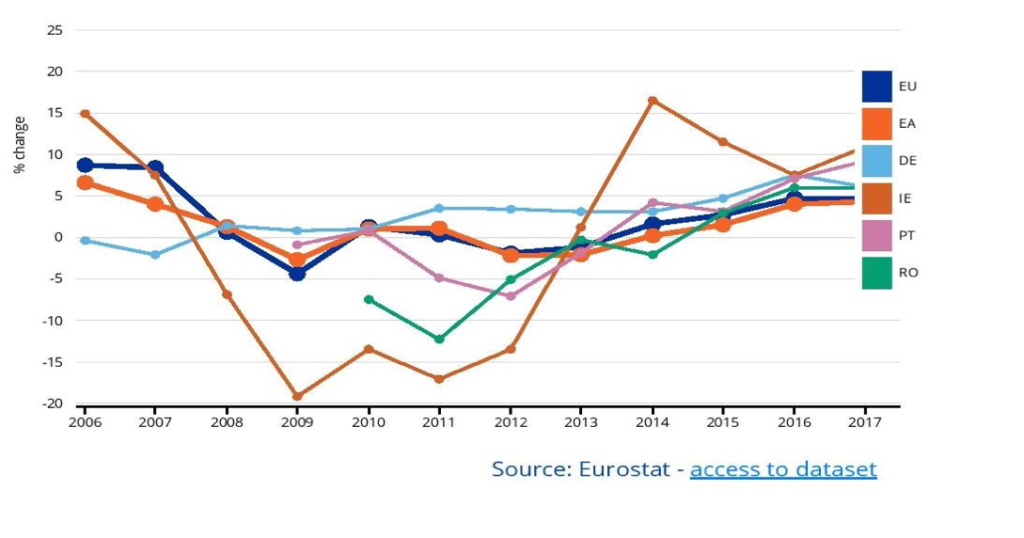

Statistical data sustain that – after falling between 2008-2009 and 2011-2013 – since 2015, housing prices continued to rise in the EU and in the Euro area (Fig. 2). In many countries, they grew with significant percentages between 2017-2018 (Fig.3), while in several countries their increase rate was higher than the EU average (Fig.4).

When it comes to identifying the causes of housing crises, the international organizations acknowledging it, continue to be in a state of denial. They do not admit that privatization, super-commodification, and financialization of housing, in parallel with the decrease of people’s purchasing power are the systemic mechanisms that (re)produce housing crises in capitalism. Subsequently, these organizations continue to promote solutions that re-enforce the privatization of public housing and housing financialization, while subordinating people’s housing needs and rights to the financial interests of private companies and banks. In this article, I will signal some new EU initiatives on the domain of housing politics, which display the tendencies mentioned above. These are issues that the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City has to address critically according to its political standpoint. According to the latter, public housing is an instrument of guaranteeing housing rights as universal rights, and taking out as many buildings and as much land as possible from the market is part of the solution to housing crises.7 Accordingly, EAC considers that the EU institutions should stop both the accumulation of homeownership in the hands of investment funds and real estate developers, and the privatization of public and social housing.8

The Housing Partnership Action Plan

The Housing Partnership was established as one of the four pilot partnerships established within the framework of the Urban Agenda for the European Union, and its members included among others Housing Europe – the European Federation of Public, Cooperative & Social Housing.9 According to the Pact of Amsterdam agreed on the 30th of May 2016 at the informal meeting of EU Member States’ Ministers responsible for territorial cohesion and urban matters,10 the objectives of this partnership were “to have affordable housing of good quality,” the material resulted from this initiative being also entitled “Affordable Housing Partnership Final Action Plan.”11 Back in 2016, the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City made a call to protest against the neoliberal policies that backed up this Pact.12 The Housing Partnership Action Plan was launched in Vienna in December 2018 during the “Housing for All” international conference attracting more than 300 affordable housing stakeholders from across the world. “This is not the official position of the European Commission”, sustains the document; however, its initiators directed their recommendations towards the EU legislators, and – acting under the umbrella of the EU Urban Agenda – are well-positioned with their endeavors. The “Housing for All” Citizen Initiative13 seems to also come to the support of the Housing Partnership Action Plan. The initiative was launched as a petition addressed to the European Commission, demanding “better legal and financial conditions in order to enable affordable housing for all in Europe,” for example by “not applying the Maastricht criteria to public investment in affordable, public and social housing,” and by “better access to EU funding for public and non-profit housing developers.”

The Housing Partnership Final Action Plan promotes a broad understanding of affordable housing, defining it as a section of a larger housing continuum including affordable homeownership, affordable rental housing, and social housing, and differentiating it from both market housing and emergency housing. Nevertheless, mostly if applied to divergent national contexts, this distinction might remain unclear. In addition, the past experience with affordable housing shows: the fact that it defines affordability linked to the market prices and not to people’s incomes, it might be a solution only for a low number of households belonging to the middle class.14

The Action Plan considers: the EU policies can have a substantial impact on national housing policies, primarily through competition rules and the application of state aid rules; while there is a lack of clarity around the implementation of state aid rules at the city level, and EU competition law limits public investment into affordable housing. The Plan aims to increase the supply of affordable housing in Europe with EU funding and European Investment Bank financing instruments. The Housing Partnership has developed a set of recommendations how to utilize EU regulations on state aid for Services of General Interest and “to ensure that state support is available for affordable housing for cities/local authorities and affordable housing providers to be able to access better housing financing conditions.”15 In parallel with these ideas, the Plan maintains the distinction between social housing for the poor, and affordable housing for the better-off population that cannot catch-up with the growing housing market prices. Further on, the Housing Partnership argues that even if the EU does not have an official mandate in the housing field, it influences national housing policies through the European Semester. Therefore, the argument continues, the EU might allow the Member States to allocate state aid as compensation for those who want to produce housing rented or sold under the market price.

At this point of the argument, one cannot stop wondering: if one demands to take out the construction of affordable housing from the competition rule and to introduce this under the spendings for Services with General Interest, why one should not apply these demands for the use of state money for producing public housing, and not for creating social housing or affordable housing by the private sector with state aid. Our dilemma is even more understandable since we know that many states with a relatively significant social housing stock (France, Netherlands, Denmark) enforce the private social housing owners to sell them on the market. If this trend continues, this means that the new housing stock planned to be made with state aid will continue to be reintroduced into the market so that public money will feed the housing market again. Besides, there are countries, where private social housing is a non-existent form of housing, and where social housing – altogether forming an insignificant percentage of the total housing stock – is in public ownership. In such countries, like Romania, the proposed regulations would be inscribed into the broad trend ongoing for three decades, i.e., the privatization of any type of housing and continuous marketization of housing as economic field. One may conclude that the Housing Partnership is a new product of the neoliberal policy context sustaining the (housing) market from public funds, and the market – uncontrolled as it is, or regulated to the benefit of large housing companies – is responsible for the (re)production of housing crises. As a result of this crises, some gain huge profits out of market speculations, while many are overburdened with housing costs and homelessness continously rises. Without a social control on the homes that it aims to support producing, the Housing Partnership remains business as usual.

The InvestEU Programme

In January 2019, the European Parliament voted the European Commission’s proposal called InvestEU Program, shaped after the model of the Investment Plan for Europe (the “Juncker Plan”). The Program “will bring together, under one roof, the European Fund for Strategic Investments and 13 EU financial instruments currently available,” and will support four main policy areas: sustainable infrastructure; research, innovation and digitalization; small and medium businesses; and social investment and skills. “Like in the Juncker Plan, InvestEU will be a part of the Commission’s economic policy mix of investment, structural reforms, and fiscal responsibility, to ensure Europe remains an attractive place for businesses to settle and thrive.”16 The EU will realize this program through a loan guarantee scheme assured from the EU budget (consisting in 38 billion Euros), which is expected to mobilize €650 billion Euros between 2021 and 2027.17 Differently put, the EU will not offer this amount of money in the form of non-refundable grants for people in housing needs across the Member States, but as a specific fund mobilizing public and private investment. As this program, unlike other EU Funds-related schemes was not technically analyzed and evaluated, it embodies a strong political will from the side of the EC under the circumstances of the shrinking EU budget and EU Funds for the 2021-2029 period.

Under the category of social investment and skills, the InvestEUProgram might be used, among others, for the construction of social housing. The banks are expected to apply for the loan guarantee budgets and at their turn they will offer loans for public authorities or private companies/ associations producing social housing. In this context, social housing provision is strictly delimited from the production of affordable housing. The European Commission expects that the European Investment Bank will be the leading actor in this process, alongside with the European Funds Bank and the Council of Europe Development Bank, but commercial banks will also want to benefit from this investment scheme.

To conclude, InvestEU looks for the involvement of banks into the creation of social housing, but – in fact – it is an extra support given to the banks and for private investments. This Program is a new step in the continuous process of housing financialization, consisting in the financialization of social housing for the poor. Or, differently put, it is a way of transforming social housing (and poverty) into a business of the financial and private housing sector.

by Enikő Vincze

Căși sociale ACUM!, Cluj, Romania [september 2019]

Footnotes:

[1] The financial burden of the total housing cost refers to the percentage of persons in the total population living in a dwelling where housing costs, including mortgage repayment (instalment and interest) or rent, insurance and service charges (sewage removal, refuse removal, regular maintenance, repairs and other charges), consist a financial burden. Related EUROSTAT data is accessible here – http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_mded04&lang=en

[2] According to EUROSTAT, this rate refers to the percentage of the population living in a household where the total housing costs represent more than 40% of the total disposable household income.

[3] Maps accessible here – https://public.tableau.com/profile/nhf.research#!/vizhome/HousingcostsintheEU_0/Overburdened, made on the base of metadata presented in the report “The State of Housing in the EU,” Housing Europe, 2017, available at: http://www.housingeurope.eu/resource-1000/the-state-of-housing-in-the-eu-2017

[4] Data on housing prices are available here – https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Housing_price_statistics_-_house_price_index

[5] https://www.statista.com/statistics/958544/house-price-index-hpi-change-in-eu-by-country/

[6] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/housing-price-statistics/visualisations

[7] See the document “For another Europe, which defends the right to housing,” launched by the EAC as a call for the newly elected EU Parliament in May 2019 (accessible here https://housingnotprofit.org/campaigns/for-another-europe-which-defends-the-right-to-housing/)

[8] See the document “European Manifesto for Public Housing: Public money for public housing – Public housing from public money,” launched by the Public housing thematic group of EAC in Cluj-Napoca, on the 29th of March 2019 (accessible here: https://housingnotprofit.org/european-manifesto-for-public-housing/)

[9] http://www.housingeurope.eu

[10] https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/decisions/2016/pact-of-amsterdam-establishing-the-urban-agenda-for-the-eu. The Pact of Amsterdam is built on a set of formerly adopted documents in the EU. Their list is presented here – https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/urban-development/agenda/urban-agenda-documents.pdf

[11] https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/housing/housing-partnership-final-action-plan

[12] https://hic-gs.org/news.php?pid=6754

[13] https://www.housingforall.eu

[14] See a brief critique on this approach at page 8 of this document of UNISON. The Public Service Union: https://www.unison.org.uk/content/uploads/2019/05/APRIL-2019-UNISON-SUBMISSION-TO-AFFORDABLE-HOUSING-COMMISSION.pdf

[17] This amount is a result of a calculus that starts from the allocation of 38 billion Euros as a budgetary guarantee (out of which 4 billion is thought to be directed for social investment and skills), to which it is expected that 9.5 billion Euros will be added by the financial partners, the resulting amount of 47.5 billion Euros being multiplied with 13.7 times (this being estimated as potential crowds in public and private investments). https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/what_is_investeu_mff_032019.pdf